How to Make the Right Choice of Tea

Aozuru-Chaho – Thés-du-Japon offers a diverse selection of unblended teas (not mixes of teas), which are made using many different cultivars (or varieties), from all over Japan. We invite you to explore the richness of Japanese tea. Admittedly, choosing a tea can be very difficult, especially for newcomers.

Here are some tips to navigate this maze of tea.

The Type of Tea

To explore Japanese tea, you should start by sencha. It is the most archetypal type of tea in Japan and the one with the most variations.

Be careful not to choose gyokuro gyokuro with the idea in mind that it is a higher quality tea than sencha. Gyokuro must be infused and consumed in a very specific way to properly enjoy. It is not better or worse than sencha, only something different that I recommend having some experience before choosing.

The Main Factors that Determine a Tea’s Flavour

Even if each tea has a unique personality, there are nonetheless broad trends in terms of flavour, which result from the different ways the teas are grown and produced.

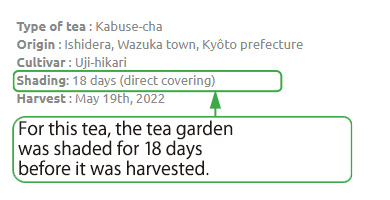

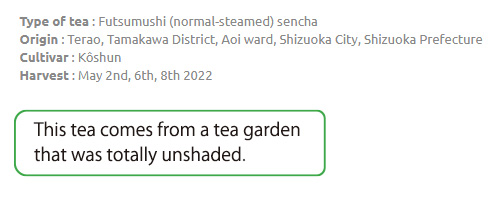

- Shaded or Unshaded Tea Gardens?

As it relates to flavour, shading a tea tree for a period of time before harvesting produces a

tea with more umami and distinct shading fragrances, reminiscent of konbu seaweed for some. Shaded teas also have very little astringency.

The technical description of each tea will specify whether or not they were shaded (if shading is not mentioned, it is an unshaded tea).

Aozuru-Chaho – Thés-du-Japon focuses on unshaded and lightly shaded teas. Heavy shading tends to reduce the character of the aromas of a tea, initial exploration could involve trying both shaded and unshaded senchas.

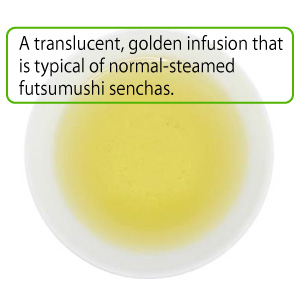

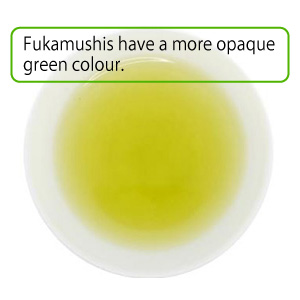

- Futsûmushi or Fukamushi Steaming

The fukamushi style of deep steaming is a newer steaming method most used in Japan, often for the wrong reasons, which has led to a lack of variation (the infusion is very green and opaque, but the flavour is not necessarily stronger). Aozuru-Chaho – Thés-du-Japon favours unique futsûmushis (also sometimes called asamushi), but still offers a selection of fukamushis.

Both futsûmushi and fukamushi teas should be tried. While it is difficult to tell which type is rounder and which is stronger, futsûmushi is more fluid and fukamushi is thicker.

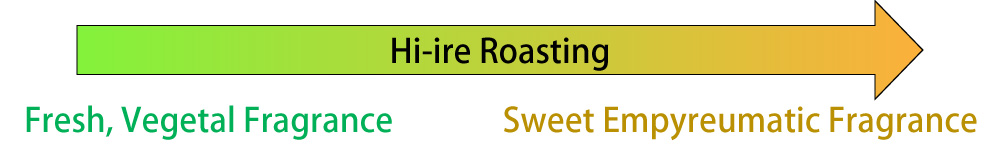

- The Roasting Process

By roasting, I do not mean the high temperature heating used for hôji-cha, but what is called hi-ire in Japanese. Hi-ire is the final drying stage that happens when finishing raw aracha tea.

Depending on the roasting strength, the same tea can have very different aromas.

Weak roasting gives a very green, vegetal, refreshing tea (noted 0 to 1 stars on the list of teas). In contrast, strong roasting produces a sweet, empyreumatic, sometimes heavy tea (3 to 4 stars).

Roasting is something I believe is especially important to consider when choosing. It is necessary to have a good grasp of the differences between these two styles of teas.

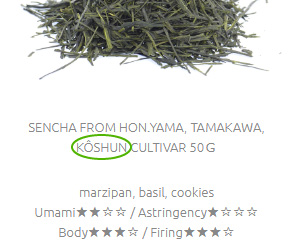

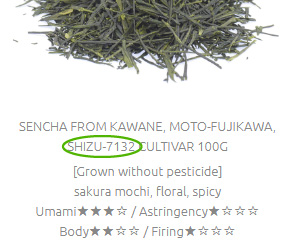

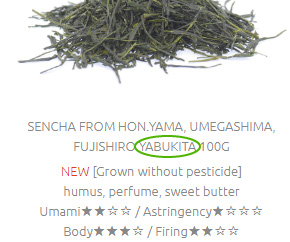

- The Cultivar

The cultivar, equivalent of a variety in winemaking, is often overlooked yet it is something incredibly important to consider, especially for a store like Aozuru-Chaho – Thés-du-Japon that offers unblended teas. To go back to the example of wine, it is not uncommon for fans of wine to give greater weight to the variety than the production region when choosing wines. Someone with a fondness for Chardonnay would probably select a Bourgogne wine, whereas someone who preferred Sauvignon Blanc would likely choose a Bordeaux.

Likewise, two different cultivars will have, sometimes drastically, different in flavours.

There are hundreds of tea cultivars in Japan, but Yabukita is by far the most common and represents 70% of the cultivated area.

Thus,

any exploration of Japanese tea should involve knowledge of Yabukita and tasting many other teas.

To get a firm grasp of the differences between cultivars, you should choose cultivars with easily recognizable strong aromatic characteristics, such as Kôshun, Shizu-7132, Yamakai, and Asatsuyu.

Lastly, it is important to understand that the same cultivar can produce very different aromas depending on how it is roasted.

- The Wilting Process

I discuss wilting at the end because it is not a well known or commonly considered part of green tea production. The process involves evaporating the moisture from harvested leaves before they are turned into tea. This is an essential stage in the production of black and oolong teas, but is generally not used for green teas in Japan. However, for the past few years, some senchas and kama-iri chas have started being wilted with the aim of producing teas with different fragrances. Wilting has successfully given some cultivars incredibly interesting aromas, such as Yume-wakaba, Fukumidori, Fuji-kaori, etc.

While it is less significant than other factors, wilting is nonetheless important to consider because of the very strong fragrances that some teas can develop from this process.

Umami? Astringency?

Finally, to return to some of the other basic considerations of taste, you should make your choice based on what you prefer, whether it be a tea with strong umami, a lot of astringency, or one that has a touch of tannins.

Obviously, these last considerations depend largely, but not entirely, on shading. There are also full-sun senchas with a lot of umami, but this umami is different than the umami from shading.

I hope these explanations will help you orient yourself and navigate through the world of Japanese tea.